The Novel Blueprint: Transforming your story from idea to final book

Learn how to transform your story idea into a polished novel with expert guidance on compelling characters, immersive worlds, and professional packaging that attracts ideal readers.

Hi,

Every writer remembers their first great idea - that electric moment when a story sparks to life in your imagination, demanding to be told. But between that initial inspiration and a finished novel lies a path that can seem overwhelmingly complex. How do you know if an idea is strong enough to sustain a full book? What makes characters leap off the page? How do you build a world that feels real while serving your story? And once you've written your novel, how do you ensure it reaches the readers who will love it?

This comprehensive guide will walk you through the entire journey from initial concept to publishable book, breaking down each stage into manageable steps. Drawing from proven techniques used by successful authors, we'll explore how to develop your ideas, craft compelling characters, build immersive worlds, and structure your story for maximum impact. We'll also delve into the crucial but often overlooked aspects of packaging your book - from writing blurbs that grab readers' attention to designing covers that communicate effectively to your target audience.

Whether you're embarking on your first novel or looking to refine your craft, these principles will help you transform your creative vision into a professionally packaged book that connects with readers. The key is understanding that while writing is an art, it's also a craft that can be learned and improved through deliberate practice and attention to fundamental principles.

***This is a long post that will be truncated in emails. I highly recommend you go to this page to read the whole 7,000-word post without interruption or download the app.***

Getting your mindset right before you dive in

Even the most brilliant concept will remain just that without the proper mental approach to see it through to completion.

Perhaps the most daunting challenge any writer faces is the terror of the blank page. That pristine white expanse can feel like an accusation, a canvas too perfect to mar with our imperfect words.

This fear is particularly acute for novelists because we're tasked with creating entire worlds from nothing - a challenge most other professions never face. The solution, counterintuitive as it may seem, is to embrace imperfection.

Begin by writing anything, even if it's stream-of-consciousness rambling. The simple act of putting words on the page helps break the psychological barrier, reminding your brain that you are, in fact, a writer, simply by virtue of writing.

This ties into a broader principle: the necessity of showing up consistently. Studies have shown that mere exposure to something, or in this case, regular engagement with the craft, naturally builds familiarity and comfort over time. Setting concrete goals, whether they're time-based or word-count-based, creates a framework for this consistency.

The key is to make these goals non-negotiable. When you commit to not leaving your chair until you've written 250 words or edited one chapter, you're training your creative mind to respond to structure rather than waiting for inspiration.

Another crucial mindset shift involves learning to embrace the cringe. Every writer, particularly at the beginning of their career, will experience profound discomfort when reading their own work. This is not only normal but actually a positive sign. It means your critical faculties are developing faster than your creative abilities can keep up.

The gap between what you can envision and what you can currently execute is what drives improvement. As you continue writing, this gap narrows, not because your standards lower, but because your skills rise to meet them.

The middle of a novel presents its own unique psychological challenges. While beginnings carry the excitement of possibility and endings promise the thrill of completion, the middle can feel like an endless slog. This "middle dread" separates the winners from the quitters in the writing world. Understanding that this feeling is universal, and that every successful author has navigated this same psychological terrain, can help you push through it. The key is to accept that the middle isn't supposed to feel exciting; it's where the real work happens.

When facing creative blocks, it's crucial to distinguish between two types: those born of simple resistance to the work (which require pushing through) and those that signal genuine problems with the story (which require listening to). The former is conquered through discipline and routine, while the latter might require strategic retreat and revision. The trick is developing the wisdom to know the difference, which comes only through experience.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, successful writers understand that process is everything. When inspiration fails, when doubts creep in, when external pressures mount, your established process becomes your lifeline. It's the set of habits and practices that carry you through when motivation falters. This means developing not just writing routines, but also systems for organizing ideas, approaches to revision, and strategies for overcoming common obstacles.

The right mindset isn't about eliminating fear or doubt. It's about learning to produce quality work despite them. By accepting the inherent challenges of the creative process while maintaining steadfast dedication to craft and routine, writers can transform their relationship with the work from one of anxiety to one of purposeful engagement.

The art of cultivating and selecting story ideas

The process of cultivating and selecting story ideas is perhaps the most foundational skill for aspiring novelists. While many writers focus on how to generate ideas, experienced authors understand that identifying and developing the right idea is far more crucial than simply generating many concepts.

The first step in this process is counterintuitive: when you have a new idea, do nothing. Instead of immediately jumping into development, let the idea prove itself through persistence.

A compelling story concept will return to your thoughts repeatedly, demanding attention and generating continued excitement with each visit. This natural filtering process might take a week, a month, or even a year, but an idea that keeps resurfacing and maintains its appeal over time has demonstrated the first sign of promise.

Only after an idea has passed this initial test should it earn a place in your development folder. This approach prevents you from becoming overwhelmed by every passing thought and ensures you're investing time in concepts that have already shown staying power. However, even reaching your development folder doesn't guarantee an idea is ready for full execution.

The next crucial understanding is that individual ideas rarely make a complete story on their own. The magic often happens when you begin combining multiple concepts from your collection. A simple premise about a "skate pod" might not sustain a novel by itself, but when merged with elements from other story seeds – perhaps a "fight or flight" scenario or a "first date" concept – it could evolve into something more substantial and unique than any of the individual pieces.

The final and most critical test for any story idea is what we might call the "spark joy" factor, but amplified to an extreme degree. It's not enough for an idea to simply interest you. It needs to generate overwhelming enthusiasm.

Ask yourself: Are you willing to spend the next one to two years developing this story? Can you envision yourself promoting it for five to ten years afterward? The project will become less exciting over time as you work through the challenges of development, so your initial passion needs to be strong enough to sustain you through the inevitable difficult periods.

Remember that passion is infectious. If you don't love your idea "a hundred and crazy percent," it's unlikely that readers will either.

The story needs to excite you so profoundly that even when it beats you down during the writing process, your remaining enthusiasm is still sufficient to carry you through to completion.

When an idea combination passes all these tests – persistence over time, synergy with other concepts, and the generation of sustained, powerful excitement – it's ready to move from your development folder into active production. This careful cultivation and selection process helps ensure that you're investing your time and creative energy in projects with the greatest potential for success.

Did you know this is available as a more in depth course inside our member area, along with over 600 other interviews, courses, articles, and book?

Three methods for building character relationships

At the heart of every great novel lies not just compelling ideas, but a carefully orchestrated cast of characters whose interactions drive the story forward. Understanding how to structure these character relationships is crucial for turning your initial concept into a fully realized narrative.

The foundation of any strong novel is the main character. Without a protagonist who captures both the writer's and readers' imagination, even the most intriguing plot will fall flat. This character becomes the linchpin around which the entire story revolves. However, it's in the careful orchestration of relationships between characters that a story truly comes to life.

There are three approaches I use to structure character relationships, each offering distinct advantages for different types of stories.

The first is the Triangle Method, exemplified brilliantly in The Matrix. Consider how the story centers on Neo as the protagonist, with Trinity and Morpheus as the two crucial supporting characters. Each brings essential elements to the narrative: Morpheus provides guidance and wisdom, challenging Neo's understanding of reality, while Trinity offers emotional connection and represents faith in Neo's potential. These aren't merely secondary characters, but carefully crafted complements to the protagonist, each illuminating different aspects of Neo's journey from confused programmer to humanity's savior.

What makes this triangular relationship structure particularly effective is how it enables multiple narrative threads to develop simultaneously. When Neo trains in the construct, Morpheus can be investigating potential threats, while Trinity monitors the real world. By separating these three main characters periodically, the story explores different aspects of its world while maintaining momentum.

What makes the Triangle Method particularly effective is how it enables multiple narrative threads to develop simultaneously. By separating these three main characters periodically, allowing them to pursue individual investigations or journeys, the story can explore different aspects of its world or plot while maintaining narrative momentum.

A key principle here is to generally keep no more than two of these main characters together at any time, bringing all three together primarily to share discoveries and advance the overall plot.

The second approach is the Ensemble Method, exemplified by works like One Hundred Years of Solitude. This more complex structure involves roughly six main characters who can be mixed and matched in various combinations. Think of how García Márquez weaves together the various generations of the Buendía family, each combination revealing new aspects of both the characters and the story's themes. Each pairing creates unique dynamics while moving the plot forward in unexpected ways.

While this method offers rich possibilities for character development and interweaving plotlines, it requires careful management to prevent the story from becoming unwieldy. For first-time novelists especially, handling more than six main characters can quickly become overwhelming. Even The Three-Body Problem, which eventually expanded to a massive cast, began with a more focused approach before broadening its scope.

The third approach, the Linear Journey Method, is often the most straightforward and therefore particularly effective for newer writers. Consider The Alchemist, where Santiago moves through his journey encountering various supporting characters – the king of Salem, the crystal merchant, the Englishman – each serving specific narrative purposes before the story moves on. While these supporting characters might reappear throughout the narrative, they don't require the same depth of development as main characters in the other approaches, as they exist primarily to facilitate the protagonist's journey toward a final confrontation or goal.

Think of this method as creating a string of pearls, where each supporting character represents a pearl the protagonist encounters along their journey. While some of these characters might be vitally important to the story, perhaps even as memorable as the protagonist themselves, they don't necessarily need to undergo their own character arcs or have extensive viewpoint scenes.

The choice between these three methods should be guided by your story's needs and your own strengths as a writer. The Linear Journey Method often proves most manageable for first novels, while the Triangle Method offers a good balance between complexity and manageability. The Ensemble Method, while powerful, typically requires more experience to execute effectively.

Remember that regardless of which method you choose, every character should serve a purpose in revealing or developing aspects of your protagonist, advancing the plot, or illuminating themes in your story.

Even in an ensemble piece, characters shouldn't exist merely to populate your world. They should each contribute meaningfully to the narrative tapestry you're weaving.

Creating main characters and villains

Once you have a framework for how your characters will interact, the next crucial step is developing those characters themselves. Let's explore a fundamental approach to character development through the lens of The Matrix, which offers an excellent study in character dynamics and development.

Every compelling character starts with a foundation of three positive traits, three negative traits, and both external and internal goals.

This simple framework provides the core from which deeper character development can grow. Let's examine Neo, our protagonist, through this lens.

His positive traits include his innate curiosity about the nature of reality, his willingness to sacrifice himself for others, and his unrelenting determination. His negative traits manifest as self-doubt, a tendency toward isolation, and initial reluctance to embrace his destiny. These traits drive his actions throughout the story and make him relatable despite the extraordinary circumstances he faces.

But what truly brings a character to life is the interplay between their internal and external goals. Neo's external goal is straightforward. He wants to understand what the Matrix is and later to save humanity from machine dominion. However, his internal goal runs deeper: he seeks self-understanding and authenticity in a world of illusions. This tension between external and internal motivations creates the rich character development that drives the story forward.

The creation of a compelling antagonist is equally crucial, and Agent Smith serves as a masterclass in villain development. The best villains are not simply evil for evil's sake. They are the heroes of their own story and often serve as a dark mirror of the protagonist. Smith's positive traits include his efficiency, his dedication to purpose, and his intelligence. His negative traits manifest as his contempt for humanity, his obsession with control, and his inability to accept change.

What makes Smith such a compelling antagonist is how he reflects Neo's own journey in a twisted way. Both characters begin to question their reality and their purpose. While Neo's questions lead him toward embracing human potential and free will, Smith's lead him toward a desire to destroy what he sees as the virus of human existence. Both characters evolve beyond their original programming, but they make radically different choices with that freedom.

This mirroring between hero and villain creates deep thematic resonance. Both Neo and Smith are, in essence, programs trying to transcend their coding – Neo as a human breaking free from the Matrix's control, Smith as an agent breaking free from his programmed purpose. The key difference lies in their response to this freedom: Neo uses it to protect others, while Smith uses it to destroy what he cannot control.

Supporting characters

The supporting characters, Morpheus and Trinity, further complement and challenge Neo's character development.

Morpheus embodies unwavering faith and wisdom, serving as a guide but also representing a kind of certainty that Neo must both learn from and ultimately transcend. Trinity represents both strength and vulnerability, challenging Neo's tendency toward isolation by offering both emotional connection and practical support.

When developing your own characters, remember that this mirroring and complementary relationship between characters creates the tension and dynamics that drive compelling narratives. Your protagonist's traits should be challenged and illuminated by both your antagonist and supporting characters, creating a web of relationships that adds depth to your story's themes and conflicts.

The key is to ensure that each character, while serving the larger narrative, remains the hero of their own story.

Even minor characters should have clear motivations that make sense from their perspective. This approach creates a richer, more believable world where conflicts arise not from arbitrary evil, but from genuine, understandable, yet opposing desires and beliefs.

Building on our discussion of character relationships in The Matrix, it's helpful to understand how different types of characters serve distinct narrative functions. We can borrow useful terminology from video games to understand these roles more clearly - specifically the concepts of "NPCs" (Non-Player Characters) and "boss characters."

In The Matrix, while Neo, Trinity, and Morpheus form our core triangle, and Agent Smith serves as our primary antagonist, the story is enriched by numerous other characters who serve different narrative purposes. Think of the Oracle as a quintessential "NPC". She doesn't directly oppose Neo, but rather provides crucial information and guidance that moves his journey forward. She presents him with choices and insights that help him understand his path, much like the Grail Knight in Indiana Jones who helps guide the hero toward their goal without serving as an obstacle.

Tank and Dozer serve similar NPC functions. They're not adversaries to overcome, but rather supporting characters who help propel the story forward through their knowledge, assistance, and contributions to Neo's journey. The same could be said for Switch and Apoc, who, while more minor characters, each contribute to moving the plot forward in their own ways.

In contrast, characters like Agent Jones and Agent Brown function as "boss" characters, intermediate antagonists that Neo must overcome on his way to the final confrontation with Agent Smith. The Merovingian in the sequels is another example of a boss character, an obstacle that must be overcome to progress the story, but not the ultimate antagonist.

Understanding these different character functions helps us create richer narratives. Your NPCs should each serve a distinct purpose in moving your protagonist's journey forward, whether through information, guidance, or support. They might test your protagonist, but their primary role is to aid development rather than oppose it. Meanwhile, your boss characters provide escalating challenges that help demonstrate your protagonist's growth while building toward the ultimate confrontation with the main antagonist.

This layered approach to character functionality, from core relationships, to antagonists, to supporting characters both helpful and hostile, creates the depth and complexity that makes stories resonate with readers. Each character type serves its own crucial purpose in the larger narrative machinery, contributing to both plot progression and character development in distinct but complementary ways.

Setting and worldbuilding

After establishing your core characters and their relationships, the next crucial element is crafting the world they inhabit. However, it's essential to understand that world-building should flow from character, not the other way around. Your world exists to challenge and test your characters, creating the perfect environment for their story to unfold.

Consider how The Matrix masterfully structures its world-building around Neo's journey. The film begins in what we might call the "starting world", the familiar reality of late 20th century urban life. This world serves several crucial functions. It establishes the status quo, introduces the basic rules of reality as the characters (and audience) understand them, and most importantly, shows us Neo in his familiar environment before everything changes.

This starting world perfectly sets up both Neo's internal and external conflicts. Internally, he feels disconnected from this reality, sensing something fundamentally wrong with the world - his famous "splinter in the mind." Externally, his hacker activities and encounters with Trinity begin to pull him toward the truth. The starting world becomes increasingly unstable as these internal and external pressures mount, eventually becoming untenable when agents come for Neo at his workplace.

The film then moves us through what we might call a transition world, made up of the initial scenes after Neo takes the red pill. This space serves as a buffer zone between the familiar starting world and the harsh reality of the "real world." In this transition, both Neo and the audience learn the new rules gradually. The construct program where Morpheus explains the nature of reality, followed by Neo's awakening in the real world, provides a crucial learning period before the full dangers of the new world must be confronted.

This structural approach to world-building is particularly effective because it follows what we might call the "10-20% rule" - only about 10-20% of your world should be completely unfamiliar to your audience.

Even in a story as reality-bending as The Matrix, most elements remain recognizable: office politics, the feel of city streets, human relationships and emotions. The truly foreign elements, the nature of the Matrix, the technology of jacking in, the physics-defying abilities, are introduced gradually, building upon familiar foundations.

Time frame also plays a crucial role in making your world digestible. The Matrix primarily takes place over a relatively compressed timeframe, which helps the audience process the radical changes in Neo's understanding of reality. When dealing with complex world-building, a tighter timeframe often helps readers or viewers maintain their grasp on the story's events and implications.

Let's examine how this escalation of world-building works in The Matrix:

Starting world: The familiar "real" world, which we later learn is the Matrix

Destabilization: Strange events and encounters begin to erode Neo's sense of reality

Transition world: The construct program and initial awakening in the real world

New world: The full reality of the human-machine war and the nature of the Matrix

Each stage builds upon the previous one, never overwhelming the audience with too much new information at once. Even when revealing the most fantastic elements of its world, The Matrix anchors them in recognizable human experiences and emotions - the universal feelings of questioning reality, seeking truth, and fighting for freedom.

This methodical approach to world-building serves the story's central character journey. Every aspect of the world exists to challenge Neo's understanding of reality and force him to confront his own potential. The world isn't complex for complexity's sake; its complexity serves the character's development and the story's themes.

Constructing the “bones” of your structure

Let's explore the fundamental building blocks of story structure, moving from the macro level to increasingly granular components. This approach to structure provides both creative flexibility and the scaffolding needed to construct a compelling narrative.

The most important thing to understand about structure is that there are all sorts of ways to build structure, and everyone seems to have their own twist on it. However, I like to start every story asking “What are the bones of the story I’m building?”

Plot and structure can be the same, but they don’t have to be. Think of the movie Hitman on Netflix. Even though it is a story about a hitman, it is built on a romantic comedy structure, meaning the two character had to end up together in the end. If they built it on the bones of a Shakespearean tragedy, then they would have had to die.

The other thing I consider before even starting to outline is the tone of the piece. Writing exists on what I call the Batman to Bugs Bunny parallel. Tone dictates what can happen in a story. You can’t have a slapstick moment in Batman Begins, and you can’t kill somebody in Bugs Bunny. If you do, you’re gonna have a bad time.

Now that we have those bits out of the way, let’s actually build our structure. At its highest level, story structure can be broken down into sequences. These are substantial chunks of roughly 10,000 words each. Think of these as similar to major sequences in film, with each sequence building to a significant turn or revelation in your story.

For a typical novel of 100,000 words, you'd be working with ten sequences. Within The Matrix, we could identify clear sequences: Neo's discovery of the Matrix's existence, his awakening and initial training, his first encounters with agents, and so forth. Each sequence fundamentally changes the story's direction or our understanding of the world.

These sequences break down into chapters, ideally running between 1,000 and 2,500 words. Each chapter, in turn, contains roughly four scenes, with scenes typically ranging from 250 to 1,000 words. This modular approach to structure creates natural rhythms in your storytelling while helping manage pacing and reader engagement.

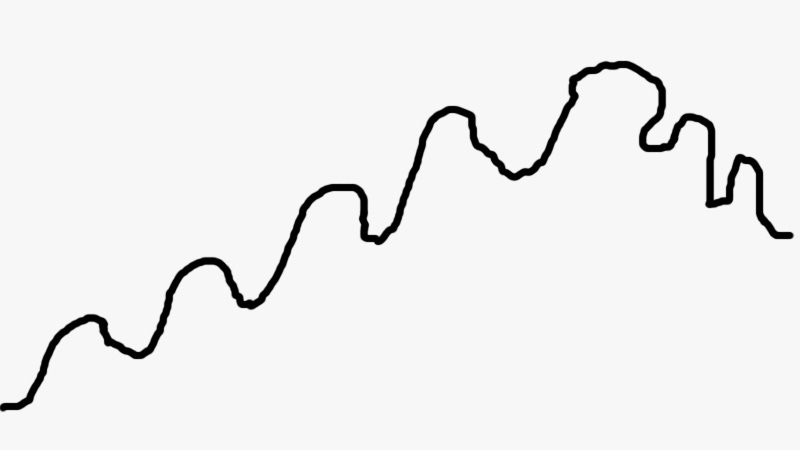

What makes this structure particularly effective is how it builds tension. Rather than following the traditional "rising action" model where tension simply escalates linearly, think of it as a series of peaks and valleys, with each peak slightly higher than the last.

In The Matrix terms, Neo doesn't simply get progressively more powerful. He experiences victories and setbacks, moments of confidence followed by new challenges that reveal how much more he has to learn.

When plotting your story, you don't need to plan every detail in advance. Instead, focus on identifying your major story beats - those crucial moments that must happen to move your story forward. These become your sequence-level turning points. The specific path between these points can remain flexible, allowing for creative discovery during the writing process. This combines the benefits of both plotting and "pantsing" (writing by the seat of your pants).

To make this process manageable, consider using the Pomodoro Technique, focused 25-minute work sessions followed by short breaks. When you're just starting out, aim for achievable goals like editing 250 words in a session. Over time, as your skills improve, you can gradually increase your pace.

Layering your plot with subplots

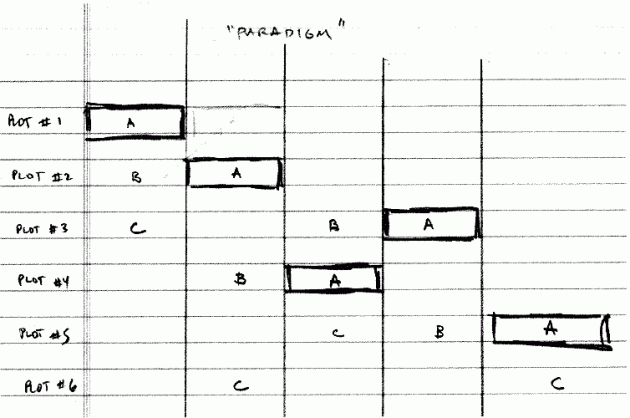

Managing subplots requires similar structural consideration. A typical novel might contain five distinct plot threads of varying importance: a primary plot (taking up about 40,000 words), a secondary plot (25,000 words), and decreasing word counts for additional subplots (20,000, 10,000, and 5,000 words respectively). Think about how The Matrix balances its main plot of Neo's journey with subplots involving the resistance movement, the nature of reality, and various character relationships.

This is brilliantly explained by Paul Levitz, in a process that is now called the Levitz Paradigm.

When working with multiple plot threads, consider how they'll evolve across a series. A subplot in one book might become the main plot of a subsequent book, creating narrative threads that pull readers through your series. Each subplot should either reach resolution within its book or clearly set up future developments.

The key to making this structure work is maintaining proper pacing within each component. Every sequence should contain a midpoint around the 5,000-word mark, followed by a larger climactic moment near 6,000 words. Every chapter sets up a new threat or challenge in its opening scene and resolves it (though not necessarily successfully) in its final scene.

Baking in your theme

Theme plays a crucial role in holding this structure together. Your theme influences not just what happens in your story, but how it happens and what it means. The tone of your work should remain consistent with your theme and inform your structural choices.

For practical purposes, this structured approach allows you to set achievable daily writing goals.

If you can write 250 words (one scene) per hour, you could potentially complete 1,000 words per day. At that pace, you could finish a sequence every ten days and a complete novel in about three months.

Remember that while this structure provides a framework, it shouldn't feel constraining. Think of it as a scaffold that supports your creativity rather than a rigid formula. The goal is to provide enough structure to keep your story moving forward while maintaining the flexibility to explore unexpected directions as they arise.

Editing your slop into something brilliant

Think of editing not as a single pass through your manuscript, but as a series of increasingly focused layers, starting with what many writers call a "garbage draft" or "zero draft." This initial transfer from outline to prose isn't really editing at all. It's about getting the raw material of your story onto the page. The term "garbage draft" is intentionally self-deprecating because it frees you from the paralysis of perfectionism. When you acknowledge upfront that this version will be rough, you give yourself permission to simply create.

Once you have your garbage draft completed, you can begin the actual editing process, which typically involves three distinct passes, each with its own focus:

The first draft focuses on major structural issues. This is where you're looking for the big problems: characters whose personalities shift inexplicably between the beginning and end of the story, plot threads that appear or disappear without resolution, or major inconsistencies in your world-building.

Think of this as examining your story's skeleton - you're making sure all the major bones are in place and properly connected before worrying about the smaller details.

The second draft moves to a more granular level. By this point, your word count should be relatively stable (around 95% of your final target), and your chapters should be in their final positions. This is where you begin "prettying up" the prose, ensuring each scene flows naturally into the next and that your pacing feels right. You're now looking at your story's musculature and how all the pieces work together to create smooth movement.

The third draft is about refinement and polish. You're now operating at the sentence level, looking for awkward phrasings, repetitive word choices, and opportunities to strengthen your prose. However - and this is crucial - you need to recognize when you've hit the point of diminishing returns.

If you find yourself making only marginal improvements rather than significant ones, it's time to hand your manuscript over to professional editors.

If you have trouble knowing when to pass off your story, you’re in good company. Many writers stumble knowing when to let go. A useful guideline is to watch for the transition from exponential to marginal improvements. When you find yourself spending increasing time making smaller and smaller changes, that's your signal to seek outside expertise.

Professional editing typically involves three stages: a developmental edit that perfects your story's structure and flow, a content edit to make sure you are consistent and everything makes sense, and a proofread that corrects the technical aspects of grammar and punctuation. Think of the professionals who handle each as quality control experts. They're there to help your book go from good to great, and then from great to exceptional.

Remember that editing is ultimately about serving your story and your readers. The goal isn't to catch every possible error - that's what proofreaders are for. Instead, focus on this essential question: "Does anything here break the illusion of the story?" If something pulls readers out of the narrative, that's what needs your attention. Everything else is secondary.

The art of blurb writing

Many authors dread writing blurbs, often spending weeks or months agonizing over them or procrastinating entirely. The key to overcoming this paralysis is understanding what a blurb is - and more importantly, what it isn't. A blurb is not a summary of your story. It's an emotional hook designed to make readers desperate to know more.

Writing an effective blurb can feel overwhelming, but having multiple approaches in your toolkit makes the task more manageable. Let's explore three distinct methods for crafting blurbs that grab readers' attention and drive sales.

The Story Core Method approach, developed by Libbie Hawker, breaks your story down to its essential elements:

Identify your main character

Define what they want

Establish what prevents them from getting it

Show how they struggle against this force

Hint at whether they succeed or fail

Using The Matrix as an example: "Neo, a computer programmer, wants to understand the truth about reality. The machines controlling humanity prevent him from breaking free. When a mysterious group offers him the chance to see the truth, Neo must risk everything to fight against the system - if he can survive becoming humanity's last hope."

This method works particularly well for character-driven stories where the protagonist's journey is central to the narrative.

The Three-Hook Structure approach uses a series of escalating hooks followed by deeper context:

Open with three ultra-short descriptions (3-6 words each)

Follow with 1-2 paragraphs expanding on the core conflict

Include who will love the book

End with a call to action

For The Matrix: "Reality is a lie. Humanity sleeps in chains. One man can wake us all.

Thomas Anderson has always sensed something was wrong with his world. When he discovers humanity is trapped in a vast computer simulation, he must become more than human to set them free.

If you love reality-bending action, profound philosophical questions, and heroes discovering their true potential, this book is perfect for you.

Get it now."

The Machine Gun Method uses a rapid-fire combination of setting, emotion, and character: [Setting] + [Verb/Emotion] + [Character] + [Description] [Second Character] + [Description] + [Stakes] [Three Questions]

For The Matrix: "A simulated world. Controlled. A hacker discovering everything he knows is a lie. A mysterious rebellion. Fighting impossible odds. With humanity's freedom hanging in the balance. Can he accept the unbearable truth? Will he become something more than human? Is he truly The One?"

Each method serves different types of stories better:

The Story Core works best for character-focused narratives

The Three-Hook Structure excels for high-concept or genre fiction

The Machine Gun Method shines with action-packed or thriller-style stories

Consider writing your blurb using all three methods and seeing which resonates most strongly with your story. Sometimes, you might even combine elements from different approaches. For instance, you might use the Machine Gun Method's setting introduction, followed by the Story Core's character focus, and end with the Three-Hook Structure's target audience statement.

Remember the core principles that apply regardless of method:

Keep it between 100-250 words

Focus on emotional connection over plot summary

Leave questions unanswered to create intrigue

Speak directly to your target audience

The best way to master blurb writing is to practice all three methods. Try rewriting your favorite books' blurbs using each approach. This exercise helps you understand how different structures can highlight different aspects of the same story.

Getting a great cover

One of the most crucial decisions you make in publishing your book is the cover. While it might be tempting to view cover design as simply an artistic choice or to cut corners to save money, your cover serves as much more than mere decoration. It's a vital communication tool that helps your book find its intended audience.

Think about the last time you browsed books online or in a bookstore. Before reading a single word of the story, you likely made split-second decisions about which books might interest you based solely on their covers. Your potential readers are doing exactly the same thing. In the few seconds someone spends scanning search results or browsing shelves, your cover needs to instantly communicate not just genre and tone, but the entire reading experience they can expect.

When readers see a cover that doesn't align with genre expectations or appears unprofessional, they assume the writing inside will reflect the same lack of understanding or polish.

This isn't about judging a book by its cover. It's about readers using covers as a reliable shorthand for finding the kinds of stories they enjoy. A romance reader knows what signals to look for in a romance cover, just as a thriller reader can spot a compelling thriller cover from across the room.

This is why studying your genre's current visual language is so crucial. Look at the top 100 books in your category on Amazon. Note the patterns: How do they use color? What kinds of images do they feature? How is text positioned and styled? These aren't arbitrary choices - they've evolved because they effectively signal to readers "this is the kind of story you're looking for."

A well-chosen pre-made cover that perfectly matches your genre's conventions will serve your book far better than an expensive custom cover that sends the wrong signals.

The real question isn't "How much should I spend on a cover?" but rather "How can I ensure my book reaches the readers who will love it?" A cover that clearly signals your genre and attracts your target audience might cost $50 or $500. What matters is its effectiveness as a communication tool. Your goal isn't to have the most beautiful or artistic cover, but to have one that helps the right readers find your book.

Remember that your cover works in tandem with your blurb and sample pages. Together, they create a promise to the reader about the experience they'll have with your book. Breaking that promise - whether through misleading cover design or poor execution - is the quickest way to disappoint readers and harm your career as an author.

So when considering your cover options, ask yourself: "Will this help my ideal readers recognize this book as something they want to read?" If you're writing a cozy mystery but your cover screams thriller, you're not just risking lost sales - you're setting yourself up for disappointed readers who wanted something different from what you're offering. The most "beautiful" cover in the world isn't doing its job if it's attracting the wrong readers or failing to attract the right ones.

Finding the right cover designer

Think of finding a cover designer like hiring an architect. You need someone who not only has technical skill but also deeply understands the kind of structure you're trying to build. Just as you wouldn't hire a specialist in industrial buildings to design your cozy cottage, you shouldn't hire a romance cover designer for your military science fiction novel.

Start by creating a collection of covers you admire in your genre. When you find covers that particularly speak to you, look up the designer. Many authors credit their cover designers in their books' copyright pages or on their websites. This research serves two purposes: it helps you identify designers who excel in your genre, and it gives you concrete examples to share when communicating your vision.

Three main paths exist for finding designers:

Pre-made cover designers: Usually, I don’t hire a designer to start from scratch. Instead, I find a pre-made cover that a designer has already made and pay them to customize it for me. This allows me to see the end product and how it will feel to find it for readers. These designers understand genre conventions and often create covers in sets, perfect for series planning. The key is regularly checking their sites as new designs appear, since good covers sell quickly.

Mid-range custom designers: These professionals typically charge $300-800 per cover and often have portfolios specializing in specific genres. They're found through author recommendations, writing forums, and professional marketplaces like Reedsy. Look for designers who showcase multiple covers in your specific genre - not just general book cover work.

High-end custom designers: Starting at $1000+, these designers often work with both traditional publishers and independent authors. They're typically found through industry connections or their own established websites. While expensive, they offer the highest level of customization and often have deep genre expertise.

Cover designers aren’t hard to find. They are literally announcing themselves on the cover of the book.

Remember, a good designer isn't just a service provider. They're a partner in your book's success. They should be able to explain their design choices in terms of market expectations and reader psychology. If a designer can't articulate why they make specific choices for your genre, they might not have the expertise you need.

Consider your cover design budget as a marketing investment rather than a production cost. A professionally designed cover that perfectly targets your audience can pay for itself many times over through:

Higher conversion rates from browsers to buyers

Better targeted advertising results

Increased reader trust in your professionalism

Series recognition leading to stronger follow-on sales

Throughout this guide, we've explored how to transform your initial spark of inspiration into a fully realized book that connects with readers. From nurturing and selecting the right ideas, to building compelling characters and worlds, to crafting effective structures for your story, each element plays a crucial role in creating a satisfying reading experience.

But having a great story isn't enough. You need to ensure it reaches the readers who will love it. This is where the packaging of your book becomes crucial. Your blurb serves as an emotional bridge between your story and your potential readers, creating an irresistible promise about the experience that awaits them. Your cover acts as a visual shorthand, instantly communicating genre and tone to help the right readers recognize your book as something they want to read. And professional formatting ensures that nothing stands between your words and your reader's immersion in the story.

Remember that every decision you make in this process should serve two masters: your creative vision and your readers' expectations.

The most beautiful prose won't find its audience without effective packaging, just as the most attractive cover won't satisfy readers if the story inside doesn't deliver on its promises. Success comes from understanding how all these elements work together to create a complete package that attracts and satisfies your target audience.

Most importantly, don't let perfectionism paralyze you. Your first book won't be perfect, and that's okay. What matters is that you're learning and improving with each story you tell. Start with strong ideas that excite you, develop them with careful attention to craft, and present them professionally to the world. Build your skills one book at a time, always keeping your focus on creating the best possible experience for your readers.

The journey from idea to published book may seem daunting, but broken down into these manageable steps, it becomes an achievable goal. Whether you're crafting your first novel or your fiftieth, these principles remain the same. Keep learning, keep writing, and keep striving to connect with readers who will love your stories.

Your next great idea is waiting.

Which aspect of your story excites you the most right now - the characters, the world, or the central conflict?

Looking at your current work-in-progress, how could you articulate its core promise to readers in one sentence?

What's one small step you could take in the next hour to move your book closer to completion?

Let us know in the comments.

If you saw value here, I hope you’ll consider becoming a paid member to help foster more of this type of thing. As a member, you’ll get access to over 850 exclusive posts, including books, courses, lessons, lectures, fiction books, and more, or you can give us a one-time tip to show your support.

I love your insistence on the characters originating the setting, not the other way around. When characters are the centre of the novel's universe, the gravity field seems more balanced somehow. Great post. Thank you.

The blurb outlines were particularly helpful! An amazing concise & thorough guide. Thanks!